Implications of Sola Scriptura

Sola scriptura is a term first applied during the Reformation period that refers to the acceptance of Scripture alone as the only infallible source of truth, and therefore the highest and final authority in all matters of faith and practice. But as alluded to in a previous post, the term means different things to different people. For Baptists, there is still a place for tradition and authorities within the church. But the importance of traditions is limited and these other authorities are delegated authorities. Also, for Baptists, sola scriptura implicitly grants the individual “soul liberty,” as there is no higher authority for the individual than Scripture. Let us take a closer look at the roles of tradition, authorities, and the individual in the Baptist faith.

The Role of Tradition

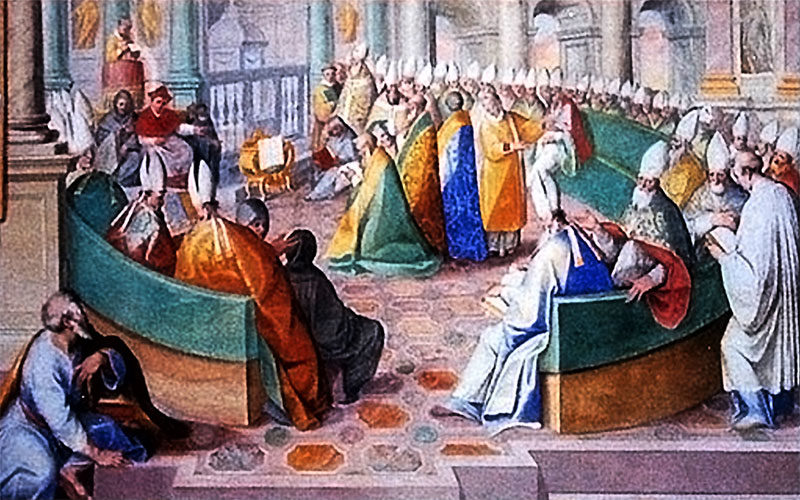

Among independent Baptists, tradition holds roughly the status of a commentary. Commentaries come in many shapes and sizes and from many theological perspectives, some more scholarly than others. But they all hold one thing in common – they are men’s opinions. Commentaries can be helpful when they expose blind spots in our own theology, when they penetrate the floor of our understanding and carry us to deeper levels of thought, or when they help to clarify complex passages or doctrines. They are like the archeologist’s brush which uncovers an exquisite artifact, or the diamond polisher’s tools that expose the brilliance of the diamond. But they are mere tools. The counsels of Nicaea and Chalcedon provided helpful statements on the nature of Christ, but they were not infallible as the Orthodox and Catholic churches believe.

In Protestantism, great weight is given to church tradition, which has been termed the “rule of faith” (regula fide). We see this in the creedal statements and confessions, such as the Westminster Confession of Faith. Protestants look back to the reformation to inform their theology, which they believe to be consistent with the teaching of the early church. In his helpful book, “The Shape of Sola Scriptura”, Protestant writer Keith Mathison has argued that Scripture, the Church, and the rule of faith go hand-in-hand and cannot be separated.1

But the problem with placing undue emphasis on tradition and insisting that Scripture be interpreted by “the Church” according to the rule of faith is that Scripture alone is infallible.

We should not assume that because a belief is old or widely held that it should be above scrutiny. One need only look at the issue of infant baptism to see that the church of the reformation was not the church of the first three centuries. Mathison cites Charles Hodge’s list of eight difficulties with placing tradition alongside Scripture, among them being the limitations of human, sinful natures; no promise by God to preserve tradition; tradition is far more difficult to interpret than Scripture; and tradition necessarily undermines the authority of, and in many cases clearly contradicts, Scripture. But these apply equally to the Protestant view of the “rule of faith.” The preoccupation of reformed theology with church history and creedal statements is only a lighter form of the Catholic claim that the Catholic Church is the custodian of tradition and therefore stands alone as having authority to interpret Scripture. The Protestant view is dangerous because it bakes in long-held errors.

Of course, it would be foolish to claim that Baptist interpretation is free from preconceptions, or is undertaken without considering the history of Baptist interpretation, or has not been colored by non-Baptist theology down through the centuries. These things undeniably influence our interpretation. In fact, Scripture commands a succession of teaching (2 Timothy 2:2). But our final appeal is always to infallible Scripture, not to church tradition, creeds, or faith statements. Only by expressly abandoning their rule of faith can a paedobaptist come to biblical convictions regarding believer baptism. Baptists intentionally bypass tradition and demand that inspired Scripture be the final arbiter in all matters of dispute. The role of tradition in Baptist thought, at the very least, allows for necessary self-correction.

The Role of Lesser Authorities

Sola scriptura does not mean that Scripture is the only authority in the life of the believer, but that it is the highest and only infallible authority. In fact, God instituted three ruling bodies: the family, government, and the church. In the church, believers are to be subject to their pastor(s) (Hebrews 13:17) and to older believers in the church (1 Peter 5:5). However these verses are understood, we can agree that there is some level of subjection to other believers and to leaders in the local church. But these authorities are God’s delegated authority. Their authority comes from Scripture, and is therefore subordinate to Scripture. This idea of delegated authority rules out the Catholic and Orthodox models of church government in which the leadership holds an authority on par with, or even above, Scripture.

In a Baptist church, Christ is the head (Ephesians 1:22), and His authority is mediated through the pastor and the church by Scripture and by the corporate indwelling of the Holy Spirit (1 Peter 2:5). Scripture presents a very short chain of command. Edward Hiscox, in his well-known “Principles and Practices for Baptist Churches,” has stated,

Christ is the only Head over, and Lawgiver to, His churches. Consequently the churches cannot make laws, but only execute those which He has given. Nor can any man, or body of men [tradition], legislate for the churches. The New Testament alone is their statute book, by which, without change, the body of Christ is to govern itself.2

Mathison defines “individualism” as autonomy of the individual, where the local church holds no real authority, and rightly labels it unbiblical. God’s model for the Christian is a healthy tension between soul liberty (being responsible for one’s own beliefs and actions in good conscience before God) and yielding to authorities in the church. The Berean believers were called “noble” because they readily received the word preached at church, and also corroborated it with Bible study at home (Acts 17:11). The church is accountable to the pastor(s) and the pastor is accountable to the church, while everyone is accountable to their head, Jesus Christ. The pastor especially will give account to God for his oversight of the church (Hebrews 13:17).

A note of application is in order here. In modern times, due to the prevalence of preachers and ministries that stream on social media, we have seen a new form of the Corinthian problem in 1 Corinthians 1:12. Church members become disciples of some prominent teacher who is in no way connected with their local church. They begin to question or instruct their pastor, adopt a prideful spirit and cause divisions in their church. They have shifted their allegiance and have become autonomous from their local body. They may claim Scripture as their final authority, but they have bypassed God’s delegated authority and undermined Christ as their Head. This causes great harm to the individual, the local pastor, and the local church. God designed the authority structure of the local church, and we must confess that God knows best and take every care to obey His instruction.

The Role of the Individual

As noted above, there must be a proper balance between individual responsibility toward God and submission to higher, delegated authorities. Either extreme leads to error. Sola scriptura does not mean total individual autonomy. God instituted the church and gave pastors and teachers for the maturation and care of the saints (Ephesians 4:11-12). There have been those in history who, because of individualism, have undermined the local church or denied orthodox teaching. The authority of Scripture in the lives of individuals grants the doctrine termed “individual soul liberty,” which means that each person is individually accountable to God and therefore has freedom to believe, worship, and serve according to his conscience. But this doctrine cannot be stretched to mean complete autonomy.

On the other hand, large segments of people claiming to be Christians today have been taught that they have no individual accountability and their sole allegiance is to their church. As reading, interpretation, and application (i.e. Bible study) is handed over to the clergy, so also responsibility and accountability. A case in point is the Catholic Church. Faithful Catholics trust their priests whole-sale and feel no need whatsoever to even read Scripture. Priests trust the higher ups without feeling the need for deep Bible study. The Catholic Church has succeeded in removing individual accountability and becoming the highest authority in the lives of the faithful.

Mature Baptists count it a great privilege to have the freedom to read, study, and meditate upon God’s Word. But with freedom comes great responsibility. Believers are responsible to ensure that Scripture holds the highest authority in every area of life. Every other influence in the world today (books, social media, news outlets, etc.) is subordinate to Scripture. Part of obeying Scripture is submitting to the authorities that God has placed there for our own good to the best of our abilities and satisfying the dictates of our consciences before God.

Conclusion

We have noted that though Scripture is the highest and final authority in the life of the church and the believer, there is still place for tradition, lesser authorities, and individual accountability and responsibility. When any of these elements are disregarded, brought out of balance, or elevated to the level of Scriptural authority, the teaching and authority of Scripture is undermined and great harm comes to the body of Christ.

Footnotes

Comments

The main issue I see with your characterizations is that there really is no “Baptist” theology, in a systematic sense. Baptists coalesce around a particular set of doctrines about the church, what it is, and how is ought to function. Beyond ecclesiology, Baptists are a grab-bag of theological positions. Your remarks about tradition, for example, likely wouldn’t be shared by Reformed Baptists who adore their 1689 LBCF!

Even among “independent Baptists,” which seems to be the group you identify with, there is no consistent theology on much of anything. Even if you stick merely to ecclesiology, try to tip-toe around in independent Baptist circles for more than 10 minutes before encountering some bastardized form of Landmarkism!

I somewhat agree with your remarks about tradition. I think you go too far when you say that the Reformed affinity for creeds and confessions is a lighter form of Catholicism. It depends on who you talk to. But, church history needs to be seriously considered. Consider the debt the church (yes, in a corporate, non-local sense!) owes to the creedal statements about the Trinity and Christology. So, for example, the doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son isn’t true because the historic creeds and confessions teach it. It’s true (or false; see Beale’s historical theology for an argument that it’s false) based on what Scripture says. But, if so many Christians believe it is true, and the creeds are historical snapshots that tell us they have believed it for centuries, then we should be very careful when we dismiss the teaching. It ought to give us pause.

In a more modern context, consider the power and pull of traditions even in a institution like Maranatha, which still obligates its students and faculty to use the KJV in the classroom.

I agree with much of what you say, but wanted to chime in with a few friendly observations. Take care!

Thank you for your comments. I don’t disagree with your “main issue” critique of my post, that there is no “Baptist” theology. I can’t think of a single systematic theology in the Baptist tradition that would be accepted across the board. But I do think we are more uniform than you might give us credit for. If nothing else, we all agree on the Baptist distinctives, and we would all claim to be fundamentalists insofar as the fundamentals can be identified.

Your observations are consistent with my assertion that we hold to sola scriptura, albeit not precisely the sola scriptura of Mathison and other Protestants. If we put more emphasis on the regula fide, we would expect to see much more uniformity among the churches.

But we are all independent, and therefore it is up to each church to decide corporately how we will believe and practice. The fact that there is so much uniformity is a testament to the perspicuity of Scripture and a generally agreed upon hermeneutic. And the differences remind us that we are all subject to Scripture and not to any other authority. It’s really quite amazing when you think about it.

Enjoyed this; thank you.