The Beginning of Fundamentalism: The Niagara Bible Conference

Spiritual forces were at work in nineteenth century Western society to undermine biblical authority and dash the blessed hope of the church upon the rugged terrain of unbelief. The twin knock-out blows dealt to the Christian denominations were Darwinian evolution and historical criticism. The only force standing in bold opposition was a remnant of orthodox believers who came to be known as fundamentalists. The first generation of those courageous pioneers gathered around a peaceful haven that served as base camp for the effort, the Niagara Bible Conference. Their initial goal was to study the Bible and seek a deepening spiritual life. The result was an equipping of soldiers for the beginning skirmishes that were breaking out in the battle for orthodoxy. The more intense fights were yet to come, but the bulwark was being raised.

Background Issues Leading Up to Niagara

The Niagara Bible Conference first met in 1876 during a period of rapid change. It was the Gilded Age, a time of economic growth and prosperity. Industry was relatively strong and the American spirit was optimistic. The religious landscape was also changing. Theological liberalism reinterpreted or denied foundational orthodox doctrines. Fundamentalism began to form as orthodox Christianity’s response.

Philosophical and scientific developments contributed largely to the liberalization of Christianity in the Western world. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species hit booksellers in 1859. His theory of evolution quickly gained widespread acceptance. Darwin’s ideas are set against a backdrop of naturalistic and humanistic philosophy set forth by men such as Hume, Kant, Hobbes, Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz. They denied the supernatural and removed the need for special revelation. Such thinking deeply undercut the authority of Scripture among liberal theologians and the general population. America at large was becoming more secular.

On the theological front, higher criticism was slowly making its way from Germany to America. Postmillennialism had been the dominant view among Protestants in America for around a century. The postmillennialism of liberals who had imbibed the higher criticism was soon divested of all supernatural elements. Meanwhile, premillennialism was on the rise in America, and with its futuristic and literal interpretation of prophecy, quickly became an important tool in the fundamentalists’ toolchest. Likewise, early fundamentalists also strongly defended the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture. At this early stage of fundamentalism, the conference was not primarily a call to battle against liberalism. Rather, it began as a call to Bible study and true biblical holiness as opposed to the notion of perfectionsim taught by the Keswick and holiness movements.1 But the attendees were also sensitive to the changing times, the attacks from liberal Christian theologians, and the secularization of American society. The men who attended the conference came from varied backgrounds, but were ready to join together in the common defense of the faith.

The Niagara Bible Conference

The Niagara Bible Conference met publicly for the first time in 1876, then yearly until 1901 (except in 1884). That first meeting was held at Swampscott, Massachusetts. The men initially in attendance that year were James Hall Brooks, Nathanial West, William J. Erdman, Henry M. Parsons, Flemming H. Revell, Philip. P. Bliss, and Major Daniel W. Whittle. The 1874 meeting was held in Watkins Glen, New York, then Clifton Springs, New York, through 1880. Old Orchard, Maine, was the location for the 1881 meeting, then Mackinac Island, Michigan, the following year. In 1883, the meeting was held at the beautiful resort area of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, for which the conference received its name. There it remained through 1897. In the last years between 1898 and 1900, the locations were Point Chautauqua, New York, and Asbury Park, New Jersey. During the intervening years, attendance continued to grow so that gatherings were as large as one thousand people or more. Meetings typically opened with a Wednesday prayer meeting, then seven straight days with five addresses per day. The Sunday schedule had a gospel message in the morning, a communion service in the afternoon, and missionary message in the evening.

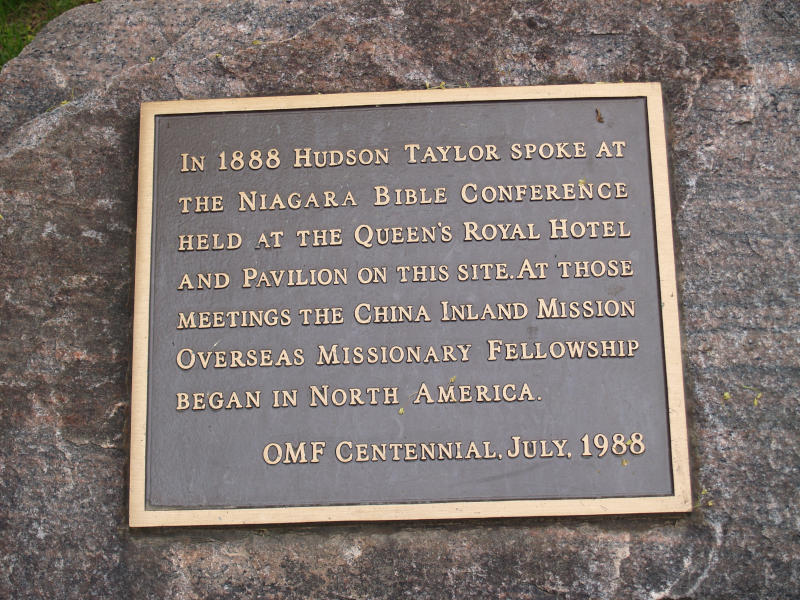

James Hall Brookes was a Presbyterian pastor and the leader of the Niagara Bible Conference until his death in 1897. His periodical The Truth was launched in 1874 and became the conference paper, carrying announcements, special news, and topical essays. The Baptist preacher of Boston, A. J. Gordon, was another key leader of the conference. He edited another conference periodical, The Watchword. One historian has called Gordon “the acknowledged patriarch of Baptist millenarians” due to his teaching and the strong influence his paper had for premillennialism among early fundamentalists.2 Canadian Presbyterian minister W. J. Erdman was secretary for the conference and was skilled in expository Bible readings. Baptist evangelist George Needham, along with James Inglis, was the founder of the conference. He continued to play a part over the years as an organizer. He also contributed messages, his wife doing the same for ladies. Miss Emma Dryer, who was long associated with D. L. Moody, conducted afternoon meetings for ladies. Other notable contributors and speakers at the conference included: Methodists W. E. Blackstone and Leander W. Munhall; Baptist Amzi C. Dixon; Presbyterians A. T. Pierson, A. C. Gaebelein, C. I. Scofield, Nathaniel West, J. Wilbur Chapman, J. Hudson Taylor; and Reformed Episcopalian William R. Nicholson. These men were prolific speakers and writers, active in soul-winning and missionary endeavors, and leaders in their own fields of ministry. For their part in standing boldly for the faith and giving early shape to the issues and methods of the movement, the men of Niagara have frequently been called the fathers of fundamentalism.

The atmosphere of the Niagara Bible Conference, helped by both the peaceful resort setting and the pietistic spirit of the attendees, was quietly devotional and spiritually refreshing. Speakers were chosen because they were “deeply versed in the ‘things of God,’” not because they were charismatic, fiery, or entertaining.3 Pietistic worship and plain exposition of the truth of Scripture were what mattered. The conference was a spiritual get-away for the attendees, and they came seeking spiritual renewal. The basis of their fellowship was the Niagara Creed, a fourteen-point doctrinal statement written largely by James Brookes in 1878. It would become well-known and later adopted in many fundamentalist churches.

The themes of the conferences, according to George Needham, were “the doctrines of the verbal inspiration of the Bible, the personality of the Holy Spirit, the atonement of sacrifice, the priesthood of Christ, the two natures of the believer, and the personal imminent return of our Lord from heaven.” Prophecy, though not the only concern of the conference, was conspicuously featured. Another prominent theme was the verbal inspiration of Scripture. Inspiration and inerrancy were foundational to having an authoritative Bible, and urgently so in the matter of literal future prophecy. A number of ministers and academics associated with Princeton Theological Seminary participated in the conference, and their academic defense of Biblical inerrancy greatly strengthened the fundamentalist position. In the last three years of meetings, the Niagara Bible Conference was in decline. A few reasons were the change of location away from Niagara-on-the-Lake and the emergence of many other similar conferences around the country which made Niagara less unique. Another contributing and perhaps more important factor was the increasing divisions among the conference teachers over the timing of the rapture.

Legacy of the Conference

The Niagara Bible Conference began with the goal of studying the Bible to defend and promote a true doctrine of sanctification, and to deepen their fellowship with the Lord. In so doing, it prepared fundamentalists for the battles that would erupt in the next few decades. It brought the primary doctrines – inspiration, inerrancy, and literal prophecy among others – to the fore, promoting and defending them. Their defense was documented and disseminated in a voluminous amount of literature. The conference emphasized sound biblical study and education, and set the stage for the emergence of the Bible institute and college movement. It spawned many prophecy conferences, the most important of which were the four American Bible and Prophetic Conferences. Those conferences, along with the Scofield Bible and limited help from The Fundamentals, made pretribulational, premillennial dispensationalism the theology of fundamentalism. The legacy of the Niagara Bible Conference lives on today in the form of the Bible conferences, fellowships, schools, mission agencies, and other fundamentalist organizations around the country and in many places of the world. Fundamentalists today owe a great debt of gratitude to those pioneers and the blueprint they, perhaps unwittingly, established for the continuing movement.4

Footnotes

- This sentence has been updated for clarification thanks to Chris’ comment below.

- Ernest R. Sandeen, “Baptists and Millenarianism,” Foundations 13:1 (1970): 21.

- Walter Unger, “‘Earnestly Contending for the Faith’: The Role of the Niagara Bible Conference in the Emergence of American Fundamentalism, 1875-1900.” PhD thesis, (Simon Fraser University, 1981), 91.

- For further reading about the development of fundamentalism, see David O. Beale, In Pursuit of Purity: American Fundamentalism Since 1850, Greenville: Unusual, 1986.

Comments

Hi Steve,

Interesting article. I am teaching on church history and am currently in US church history during the time around the US Civil War, so will soon, Lord willing, be teaching on the fundamentalist battles.

I think you would do well to define “the deeper Christian life.” You referenced it several times and I think it is one of those concepts we all have an idea of, but widely vary in our understanding of. Do you mean Keswick Theology?

Also, I did not know that J. Hudson Taylor was a speaker at these conferences.

Thank you for your efforts! God bless you!

Grace,

Chris Best

Hi Chris, Thank you much for your feedback!

According to my understanding, the organizers and participants of the conference were looking to deepen their devotion to the Lord, and at the same time to establish a positive doctrine of sanctification. The conference specifically started, in part, as a Bible study meant to counteract the Keswick and holiness movement teachings of total sanctification and the second blessing, although both of those movements were undoubtedly influential on the participants of the conference. I should have made that more clear. Thank you for pointing that out.

See Unger’s discussion referenced in the second footnote, specifically pg 32f. You can read it for free here: http://summit.sfu.ca/item/4002.

By the way, if you want to contribute any articles from your studies, you are more than welcome to post them here. I am always looking for more contributes!